Saturday, April 19, 2014

What Really Took the Children of Hamelin?

Everyone has heard some version of the 16th Century tale "The Pied Piper of Hamelin." However, if this is unknown to you, the story is as follows -

A small German Hamlet known as Hamelin (Hameln, more accurately) is plagued by rats. No matter how diligently they try, the townspeople cannot get rid of all of the vermin. One day, an odd man dressed in bright clothes appears and offers to rid the town of the rats for a fee. The town agrees and the man produces a flute or fife and begins to play. The rats scamper out of hiding and begin following the Piper out of town. He leads them to the edge of a cliff by the ocean and like lemmings, jump off and drown themselves.

When the Piper returns to the town to collect his fee, the mayor spurns him. There are no more rats so why should the Piper be paid? The Piper returns to the street and begins playing again. This time, the town's children begin following him. He leads them out of town up to a misty mountain and none of them are ever heard from again.

It is accepted that many of these old tales had some basis in fact. For example, the children's song "Ring Around the Rosey" being a song about the plague is very familiar. So, who was the Pied Piper and what happened to the children?

There are many, many theories about the tragedy that befell Hameln; everything from Holy War to plague to relocation has been offered to explain the disappearance. However, a recent discovery of 14th Century writing discovered at Hameln Monastery may shed some light upon what truly happened.

During a renovation in 2010, a hidden manuscript was found wedged between bricks in the Southwest wall. According to the workers, had there not have been an accident that knocked the stone, it would never have been investigated. The block was removed to be cleaned and reset when the hollow behind it was revealed. In a fairly well-preserved wooden box were over 100 handwritten pages.

Even though the brightest German archeologists and theologists were called immediately to the site, many of the pages were too frail to preserve but many have been painstakingly repaired.

Years of study have not revealed the author of the pages, a few bear the name "Friedrich" signed at the bottom. They are not illuminated, but are in the same hand that illuminated many bibles of the region and time. Consequently it is impossible to name the individual monk responsible for this journal since monks were trained to write as identically as humanly possible to keep the consistent appearance of the holy books they transcribed.

Much of what was written by this mystery-monk was personal: reflections on his commitment to the order, reminisces of his family, etc. Yet, he did take the time to record some of the history of Hameln during Friedrich's impressive 67 year life.

One tale of interest was of a group of townsfolk, made up primarily of merchants, who were being taxed by the local town council led by Baron Ernst Von Bonninghausen. The strategy was to reduce these merchants to poverty, buy their businesses, and transform them from owners to employees. Having approached the church for assistance, the priest could offer no assistance since the church's major benefactors were the council themselves.

The story continues that a trio of representatives of the oppressed merchants went to the outlying woods to consult with a witch. They asked her to rid Hameln of the Baron and his cronies. The witch agreed but for a price. She wanted three of their children in return for her services.

Initially the merchants were offended. Offering the lives of three children in sacrifice as a solution to their problem was outrageous. They left the witch's lair without signing the covenant. However, upon their return journey back to Hameln, one of them was struck with an idea: They would make the deal with the witch, the Baron and his people would be driven out, and then the townspeople would then capture and kill the witch.

The trio returned to the witch and the deal was struck. The witch advised that all of the townspeople be locked behind door and shutter the next night.

As the monastery bell tolled midnight the next evening, the town council, still dressed in their bedclothes, assembled in the square along with the Baron. Their eyes were open but sightless and they shuffled out of town only to be discovered the next afternoon, all lying, broken amongst the rocks at the bottom of a gorge.

The frightened townsfolk had not counted on murder as the solution for which they had bargained. They thought the council would be beset by an affliction or shame that would drive them from the town rather being killed mercilessly. They gathered with pike, pitchfork, and torch and set out to kill the witch.

When they arrived at her hut, she was gone. The only communication was a word scratched in the door: "Drei" (3). The enraged townsfolk searched the woods but to no avail. The witch had vanished. That night, the children of Hameln were tied to their beds while their parents stood watch.

However, the next morning, three sets of bare-footed, children's feet prints were discovered. They led out of town into the woods where the trail was lost. The children were never seen or heard from again.

From what can be ascertained, this could be the FIRST telling of the facts that over time, became the tale of the Pied Piper. Instead of rats, we have politicians. Instead of all of the children in the town vanishing, only the three promised as payment.

The fairy tale of "The Pied Piper" never painted a positive portrait of the people of Hamelin. Their greed and love of money cost them the lives of their children (although in more recent interpretations of the story, the repentant townsfolk agree to pay the Piper and their children are returned. Hence the expression, "You have to pay the Piper"). Alas, it is the spreading of the responsibility to all of the people and the threat of everyone losing that makes the story a more effective cautionary tale.

Tuesday, April 8, 2014

The Truth Behind "Beelzebub"

There is a popular misconception amongst Westerners that "Beelzebub" or "Beezlebub" (as it is sometimes misspoken) is an alternate moniker for Satan. Whilst it is true that Beelzebub has become synonymous with the Lord of Darkness, the true nature of Beelzebub can be traced much further back, than the Christian Bible, to ancient Babylon.

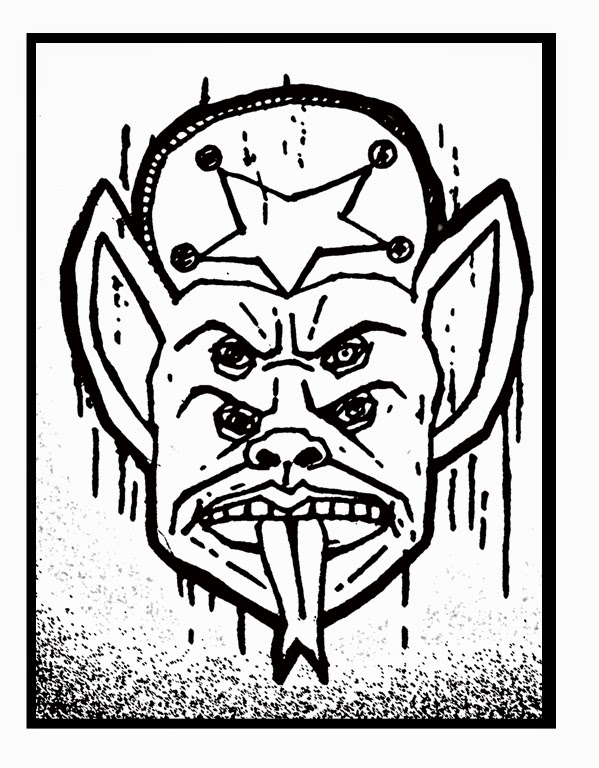

Ancient cuneiform tablets speak of "Baelzepeth" a lower demon said to be able to be conjured from the depths of hell to serve those who would call him. He is represented in ancient art as being chained either at the ankle, wrist, or in some cases, with a collar locked around his neck. This represents Baelzepeth's inability to act independently when called.

Baelzepeth could be freed, but only when he carried out six tasks: First, he had to kill four humans by the use of the elements, air, earth, fire and water. After each death, he would receive a gift in the form of a special ability to assist him with his efforts. Freedom would be granted only when he had managed his last two assignments: The death of a selfless person, and the corruption of a good person. Once Baelzepeth had completed these tasks, his "chain" would disappear and he would become a significant demon, capable of independent thought and action.

Although, historically, there has been no account of Baelzepeth being summoned purposefully, it was accepted amongst the Babylonians that only a necromancer could bring forth or send back Baelzepeth from the underworld.

Through the Babylonian influence on Ancient Hebrew mythology, Baelzepeth became "Baal" and "Zebub" two demonic brothers that were feared amongst the tribes. There has been speculation amongst scholars whether or not, Baal was the demon that had been released by God to kill the first born of Egypt since Heavenly beings would not participate in cold-blooded killing. Technically Baal is the word for "Lord" and could be extended to both Earthly and un-Earthly beings. However, those who fled Egypt after the plagues whispered in shadows of Baalzebub who had been sent by God to reign down terror upon their captors. Baal-zebub translated means "Lord of the Flies" and it was not by chance that flies, locusts, and other forms of pestilence had been part of the Hebrew liberation.

By the time of the Crusades, Baalzebub was feared equally amongst the Muslims and the Hebrews. As Templar Knights returned to Europe during the Crusades they related exaggerated tales of Baalzebub or "Beelzebub" as it was misinterpreted.

When the Black Plague broke out during the High to Late Middle Ages, some attributed it to the influence of Beelzebub, brought to Europe through the spoils of the Holy War. Strengthening the argument for conquest over the dark forces, Beelzebub became accepted as another name for Lucifer (who's name ironically means "bringer of light"). The traditional Babylonian visage with its frightening teeth and pointed ears then had horns added for greater effect.

As centuries past, Beelzebub became associated not just with Satan, but with Satan as followed and served by witches and warlocks especially in Celtic traditions. It does not take a huge leap of logic to understand how Beelzebub crossed the Atlantic Ocean in the minds of pilgrims to set foot in the New World.

Women and men who possessed the sign of the upside-down pentagram were said to be "touched" by Beezlebub whose fingerprints revealed the sign of the five-sided star and as history revealed, these people were destroyed as witches. Although many were innocent, a few genuine "Beelzebub worshipers" have been documented and according to surviving records, their descendents live amongst us today.

Ancient cuneiform tablets speak of "Baelzepeth" a lower demon said to be able to be conjured from the depths of hell to serve those who would call him. He is represented in ancient art as being chained either at the ankle, wrist, or in some cases, with a collar locked around his neck. This represents Baelzepeth's inability to act independently when called.

|

| Baelzepeth depicted on an Ancient Babylonian tablet. |

Although, historically, there has been no account of Baelzepeth being summoned purposefully, it was accepted amongst the Babylonians that only a necromancer could bring forth or send back Baelzepeth from the underworld.

Through the Babylonian influence on Ancient Hebrew mythology, Baelzepeth became "Baal" and "Zebub" two demonic brothers that were feared amongst the tribes. There has been speculation amongst scholars whether or not, Baal was the demon that had been released by God to kill the first born of Egypt since Heavenly beings would not participate in cold-blooded killing. Technically Baal is the word for "Lord" and could be extended to both Earthly and un-Earthly beings. However, those who fled Egypt after the plagues whispered in shadows of Baalzebub who had been sent by God to reign down terror upon their captors. Baal-zebub translated means "Lord of the Flies" and it was not by chance that flies, locusts, and other forms of pestilence had been part of the Hebrew liberation.

By the time of the Crusades, Baalzebub was feared equally amongst the Muslims and the Hebrews. As Templar Knights returned to Europe during the Crusades they related exaggerated tales of Baalzebub or "Beelzebub" as it was misinterpreted.

|

| After Montgomery, 1957 |

When the Black Plague broke out during the High to Late Middle Ages, some attributed it to the influence of Beelzebub, brought to Europe through the spoils of the Holy War. Strengthening the argument for conquest over the dark forces, Beelzebub became accepted as another name for Lucifer (who's name ironically means "bringer of light"). The traditional Babylonian visage with its frightening teeth and pointed ears then had horns added for greater effect.

As centuries past, Beelzebub became associated not just with Satan, but with Satan as followed and served by witches and warlocks especially in Celtic traditions. It does not take a huge leap of logic to understand how Beelzebub crossed the Atlantic Ocean in the minds of pilgrims to set foot in the New World.

Women and men who possessed the sign of the upside-down pentagram were said to be "touched" by Beezlebub whose fingerprints revealed the sign of the five-sided star and as history revealed, these people were destroyed as witches. Although many were innocent, a few genuine "Beelzebub worshipers" have been documented and according to surviving records, their descendents live amongst us today.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)